Megan Saltzman presented her new book–Public Everyday Space: Cultural Politics in Neoliberal Barcelona–which explores how everyday practices in public space (sitting, playing, walking, etc.) challenge the increase of top-down control in the global city. Public Everyday Space focuses on post-Olympic Barcelona—a time of unprecedented levels of gentrification, branding, mass tourism, and immigration. Drawing from examples observed in public spaces (streets, plazas, sidewalks, and empty lots), as well as in cultural representation (film, photography, literature), this book exposes the quiet agency of those excluded from urban decision-making but who nonetheless find ways to carve out spatial autonomy for themselves. Absent from the map or postcard, the quicksilver spatial phenomena documented in this book can make us rethink our definitions of culture, politics, inclusion, legality, architecture, urban planning, and public space.

About the speaker

Megan Saltzman (PhD, University of Michigan) is a teaching professor at Mount Holyoke College in the department of Spanish, Latin American, and Latinx Studies, where she also contributes to the Five Colleges of Massachusetts Architectural Studies Program. Her research focuses on contemporary urban culture of Spanish cities with a transnational and ethnographic approach. Her 2024 book, Public Everyday Space: Cultural Politics in Neoliberal Barcelona combines literary and visual arts with fieldwork to expose how everyday practices in public space (sitting, playing, street selling) not only challenge the city’s policed image but also serve to carve out autonomy from below. Megan has published on urban cultural themes in Spain related to gentrification, spatial in/exclusion, immigration, nostalgia, recycling, urban furniture design, grassroots cultural centers and “artivism.” Most recently Megan has been teaching courses that revolve around three themes: (1) urban studies, (2) material and non-human culture, and (3) ethnically hybrid identities. Besides teaching at Mount Holyoke, Megan has enjoyed teaching at a variety of colleges, including the University of Otago (New Zealand), Grinnell College, the University of Michigan, Amherst College, West Chester University, and this coming fall at Sophia University in Tokyo.

Video of Public Everyday Space: Cultural Politics in Neoliberal Barcelona with Megan Saltzman

Transcript of Public Everyday Space: Cultural Politics in Neoliberal Barcelona with Megan Saltzman

0:00:08.8 Tom Llewellyn: Welcome to another episode of Cities@Tufts Lectures, where we explore the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities designed for greater equity and justice. This season is brought to you by Shareable and the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University, with support from the Barr Foundation. In addition to this podcast, the video, transcript, and graphic recordings are available on our website, shareable.net. Just click the link in the show notes. And now, here’s the host of Cities@Tufts, Professor Julian Agyeman.

0:00:41.4 Julian Agyeman: Welcome to our final Cities@Tufts virtual colloquium this semester. I’m Professor Julian Agyeman, and together with my research assistants, Amelia Morton and Grant Perry, and our partners Shareable and the Barr Foundation, we organize Cities@Tufts as a cross-disciplinary academic initiative which recognizes Tufts University as a leader in urban studies, urban planning, and sustainability issues. We’d like to acknowledge that Tufts University’s Medford campus is located on colonized Wampanoag and Massachusetts traditional territory. Today, we’re delighted to host Dr. Megan Saltzman. Megan teaches at Mount Holyoke College. Her research combines literary and visual arts with ethnographic fieldwork to expose how everyday public practices, carve out autonomy and resistance from below. Megan has published on urban culture in Spain related to gentrification, spatial inclusion and exclusion, immigration, waste, urban furniture, grassroots cultural center, and artivism. These themes come together in Megan’s most recent publication, her book Public Everyday Space: The Cultural Politics in Neoliberal Barcelona. And that is the name of her talk today. Megan, a Zoom-tastic welcome to Cities@Tufts.

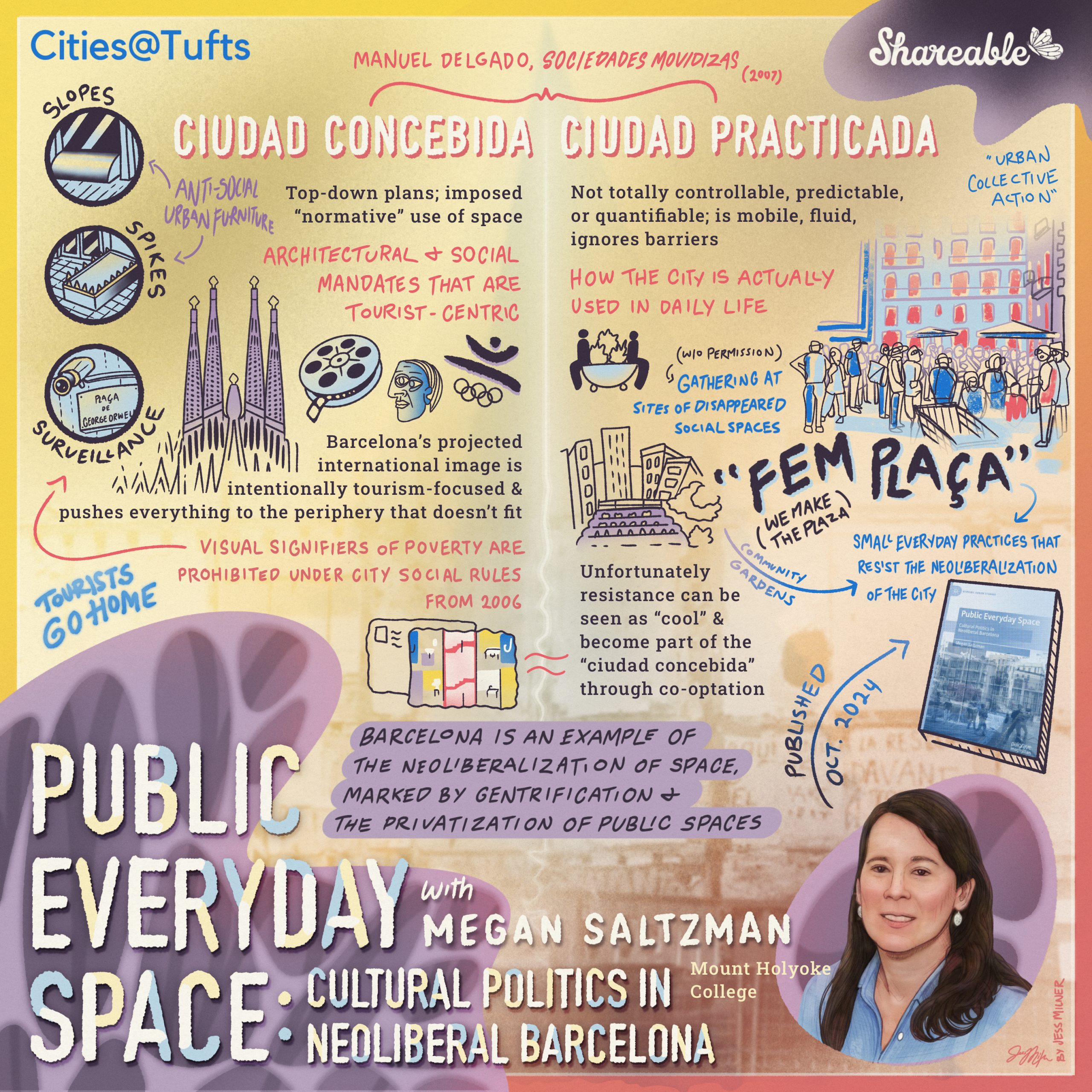

0:02:04.5 Megan Saltzman: Okay, thank you very much, Julian. Thank you for the invitation and also thank you, Tom, for all the tech assistance. And also I want to thank Mount Holyoke College in general for the support in the process of writing and finishing this book project. Okay. Well, I’ll start by saying that free, accessible, open public space is not what it appears to be. In fact, it’s often, especially in the city, the opposite of what it appears to be. Nevertheless, we read the city as a truthful or objective text absorbing knowledge, ideas, norms, and feelings from our public surroundings. Today’s public spaces are designed in a way that very carefully regulates what we can see, what we can do, and what we can know in it. For example, its design prioritizes a limited number of activities such as facilitating formal work or consumption, buying stuff, and also transit, moving individuals, human individuals, quickly from point A to point B. And so today’s public space is designed in such a way to make us think, again, that it’s free, open, and accessible to all. Urban anthropologist Manuel Delgado points out two cities that are coexisting. We have the planned and conceptualized city on a powerful scale, like architectural plans, institutional policies, these top-down initiatives, and imposed normative use of public space.

0:03:43.2 Megan Saltzman: And then we also have what he calls the ciudad practicada. It’s how it’s actually used in daily life, on the ground, everyday practices. It’s something that’s not totally controllable or predictable or quantifiable. It’s mobile, fluid, and it often ignores barriers or lines. So one of the goals of my book is to expose what’s being intentionally limited from view, what the ciudad concebida is limiting from our view and from our possibilities, as well as expose the potential of public space, of the ciudad practicada, that everyday city buzz in the background that circumvents being controlled and quantified. So my book’s main focus is on the small everyday practices that resist the neoliberalization of the city. And for those of you who may be new to these concepts, I understand that this might be very condensed or packed. So let me unpack these concepts, starting with the neoliberalization of Barcelona. By that, I’m referring to the rapid and destructive changes that were undemocratically imposed in the last four decades in Spain and in most Spanish cities to create and maintain this ciudad concebida. And this, in Barcelona especially, dramatically rebuilt central areas of the city, making it unrecognizable for many and economically exclusive for the majority of locals.

0:05:20.4 Megan Saltzman: So what specifically contributed to the neoliberalization of Barcelona? Well, there’s the privatization of public space of the last couple of decades. And I wanted to point out, ’cause I imagine a lot of you are tuning in from Boston, I think these characteristics of neoliberalism that I’m about to name will definitely resonate with those in Boston and in many global cities and major US Cities. But I want to point out that in the case of Spain and Spanish cities, a lot of these neoliberal characteristics or aspects and initiatives are still not normalized. It’s still relatively new. Things that started to happen in the 1990s, for example. So a step behind the neoliberalization of public space, I would say, in the United States and in US Cities. So yeah, the privatization of public space and also the construction of a tourist image of the city, a very narrow, profitable visual definition of the city, equating the city to a brand, the city branding. And in the case of Barcelona, city branding is very strong. You can just stick the word Barcelona into Google Images and you’ll see a billion pictures of Gaudi architecture and the Sagrada Familia, a very monumental architectural definition of the city.

0:06:47.6 Megan Saltzman: And I wanted to show here, since I’m coming more from cultural studies, from arts and film and literature, that culture, the arts, the humanities, which often are underfunded and defunded and not paid much attention to, were actually an important component of these changes in Barcelona, the neoliberalization of the city, the gentrification going on in the city. And here we have an example of the Woody Allen film Vicky Christina Barcelona, one of many films that helped disseminate this global architectural image of the city. And Woody Allen was paid several, one and a half million euros in public funding to showcase Barcelona’s architecture in public spaces. And also I include this image of the Olympics because most of these initial transformations started in preparation for the 1992 Olympics. And again, in the background, you can see this monumental view of the monument. Yeah, the arts are part of this neoliberalization of the city. And also another important aspect has been the creation and maintenance of a wide control apparatus to protect the tourist industry, to protect this new global economy. And part of this control apparatus has been an increase in surveillance, all types of surveillance, more video cameras in public space, more police presence, security guards.

0:08:16.9 Megan Saltzman: And also, for example, in 2006, the city hall, city council came out with a very long document, something like 80 or 90 pages of civic rules of how people need to behave in public space. And this is a city that was not used to having so many rules in public space. But to give you an example of some things that were suddenly in 2006 illegal, unless some kind of previous permission was granted, for example, no sleeping in public space, no drinking alcohol in public space, no begging, no distributing food, no peddling, no throwing up, no painting, no skating, no sex work, no hanging objects, objects from balconies, no hanging posters or banners in the plazas or streets, no taking anything out of the trash, no playing music. And the list goes on and on. And again, perhaps from a US point of view, this could for many seem normalized. But in the case of Spain and a long history, which I think is true in many Mediterranean cities, of a certain informality and organicness in the public spaces, even in times of dictatorship, this was really a shock. And the book is looking at the pushback against this kind of regulation of behavior and appearance of public space.

0:09:50.1 Megan Saltzman: So here I can show you, for example, this is just ironic that in the Plaza de George Orwell, you can see a sign that there’s a video camera there. And here’s some photos that I took of also the implementation of anti-social urban furniture in the public space to, again, control and nudge and mold what we do and who can be, who can rest, who cannot rest. And this idea of moving along public space merely for transit, merely for work and consumption. Okay. This one… This was a particularly interesting type of construction where it was like an inverted slide. So if you tried to sit on this, you would just plop off. Okay. So yeah, another part of the neoliberal was the anti-social urban furniture, which we’re seeing popping up all over cities. Following what urbanist Don Mitchell calls the landscapes of pleasure, these controls have ended up eliminating, displacing, or pushing to the periphery everything that does not fit the tourist image, which means everything that’s not profitable or for maintaining the ciudad concebida. So what has been pushed out of view or destroyed?

0:11:18.9 Megan Saltzman: Well, hundreds of historical working-class buildings, many of them from the 18th and 19th Centuries, and with those buildings, much of their history also disappears. Small businesses, the communities. In many of these Mediterranean cities, we’re talking about very dense space, long-term communities. These central downtown communities have been fragmented. Also, they have tried to push poverty or anything that could be associated with poverty out of view. Spontaneity has for the most part decreased. A lot of the benches, in terms of urban furniture benches, especially the traditional long bench, has decreased in central areas. Informal markets and informal economies, which have a long history in Barcelona, have been cracked down on. And places that look dirty or smell bad have also been eliminated or pushed out of view. And I have… I found this like little zine that illustrates an idea. In doing a lot of the interviews for this project, when I spoke with elderly people specifically, they often spoke of a sense of disorientation resulting from these changes, of not knowing where they were within their own neighborhood because the buildings had transformed so quickly. And so in this zine in Spanish, I have it here down in English. It says, the neighborhood has suffered from gentrification and Mrs. Amalia, after living there for 42 years, has to move because she can’t afford the rent.

0:13:06.4 Megan Saltzman: Can you help her find the exit to the periphery? So this is one of many examples of the cultural responses that I have in my book related to these changes. And also I know some of you all are studying about sustainability in contemporary cities. There’s the whole ecological factor to consider. Barcelona is a small city, compact historical city, and they’re receiving 16 million tourists a year. So it doesn’t have the infrastructure to sustainably welcome or deal with this level of tourism and the amount of water and waste and air pollution that it creates. And also just in these last couple of weeks, there’s been massive protests in Barcelona because all of these processes, the gentrification processes, have skyrocketed the rent and the price renting a home or buying a home, especially in terms of Airbnb and tourist apartments. Going back to this goal, small everyday practices that resist the neoliberalization of the city. So small everyday practices, what I’m referring to with this is a type of small resistance that receives little attention and often goes unnoticed.

0:14:28.9 Megan Saltzman: When we think about political resistance, for example, we tend to think of larger phenomena like protests or social movements or activists, I mean, in terms of people, activists or well-known intellectuals or certain politicians. And that’s good. That’s important. In Barcelona’s case, those types of forms of resistance have already been well documented with books and analytical studies. And so I didn’t feel that I had too much to offer along those lines. So I wanted to focus on a less discussed type of resistance and agency, this type that we can find in everyday practices. And this type of small resistance emerges from lesser known spaces in the city, the everyday spaces like streets, plazas, street corners or abandoned lots. And I found that many of the examples of this type of small resistance are non-confrontational, they’re non-violent, they at times can be joyful or leisurely, they’re often anonymous and very accessible, something that anybody can do. And also I noticed that this type of resistance in Barcelona, we could call it, so to say, weak or weaker because it’s temporary and it’s not loud or eye-catching, it’s quite fragile. But nonetheless, it does challenge and provide nuance to the dominant destructive tourist image and objectives of today’s urbanism in Barcelona because it exposes a difference.

0:16:15.6 Megan Saltzman: And so in doing the research for this book, I think the closest theoretical description that I could find was Deleuze and Guattari’s metaphor of the rhizome. I’m not sure if some of you are familiar with that, but to sum it up, a rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines or on a new line or on new lines. And these lines always tie back to one another. So this idea of this small resistance that’s temporary, it’s flexible, it’s regenerational, mobile, elusive, like a worm or an octopus, if it gets squashed or eliminated, it can return or it can regrow its parts. So the practices can return if they’re pushed to the periphery. They can return maybe in a different place or at a different time, but they’re able to continue. And so I found that a focus on everyday practices opens up a whole other level of coexisting realities in the city, a place where we can still find some spontaneity, creativity, community, and democratic practices. We can find people carving out space and autonomy for themselves in difficult circumstances where they might not be able to have a voice or have communication with politics with the capital P, institutional level of politics.

0:17:45.5 Megan Saltzman: And also that these everyday practices allow us to see the flexibility and the potential of our urban materials beyond just a singular conventional use of, for example, a bench or a curb. So with the remaining minutes, I will quickly summarize the rest of the chapters, which again, all focus on different types of small everyday rhizomatic practices that go against the grain of what philosopher Jacques Eancière calls the order of things, the order… The normal order of things in the city. Okay, so the next chapter and also the book cover image is this one here, which is actually two superimposed photos on top of each other, one that I took and another a friend took one year later. One day I was just wandering around the central area, the neighborhood called the Raval, and I noticed a group of men, what I assumed to be men, playing volleyball within an abandoned lot. And I was curious as to how they got in there because it was completely fenced off and there’s also these cement blocks around the abandoned lot. And I found this hole, I don’t know, about like 12 inches by 12 inches.

0:19:13.7 Megan Saltzman: And so I thought, ah, okay, so they must have put their bodies through this hole and the volleyball net, the ball through this hole. And I had been reading a lot about Michel de Certeau and his book, The Practice of Everyday Life, and his idea about spatial tactics and how we can repurpose things, in this case, repurposing urban materials and giving them a different function, some unplanned function. And so I decided that many of these practices, small practices of resistance that I was seeing in Barcelona fit under this category of spatial tactics, of repurposing one’s urban material surroundings, having to re-adapt to the destruction in one’s neighborhood and the privatization and the hyper-regulation of one’s urban surroundings. So I found a lot of examples like this. I remember, for example, with the economic crisis of 2007, 2008, it hit Spain very hard. Unemployment, for example, for youth was… For younger people, was over 50%. And there was much more poverty in the city. And with that poverty, I started to see more and more spatial tactics like those ATM bank rooms where you have to swipe a card to get in.

0:20:37.1 Megan Saltzman: I noticed at night that people would go into these ATM rooms and convert them into bedrooms for sleeping at night. Or another example was in Spanish cities, you have these very large trash dumps that are on the sidewalk. And I noticed that next to these big trash dumps, people would carefully leave piles of things that other people might want to use or have or recycle. What else? Also with the elimination of benches, I saw people using all sorts of things in the city, material things in the city to create places to sit. As you can see here, these people have turned a big plant pot into a sitting place, as well as here, this kind of shop ledges turned into benches. Or this example here, it was a person who had created some kind of exercise equipment out of what? Out of these poles to stop cars from coming onto the sidewalk. Okay. And also in this chapter, I focused on a film, which I highly recommend. It’s called En Construcción. And in this film, we can see a wide variety of spatial tactics and not only from human beings, but also in animals and how they all try to adapt to these rapid material changes in the city.

0:22:10.3 Megan Saltzman: Okay. And then the next chapter is about collectives or groups and self-managed spaces that emerged after this economic crisis, the recession. It takes a look at groups that have taken it into their own hands to create their own public spaces independently and the impact that these have had locally and abroad. So these were the ones… What I saw was a boom in around 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013. There was a boom of these self-managed, in Spanish, the word is easier, it’s autogestionado, which is a common word for some… It’s a bit like DIY, do it yourself. If the government is not going to pay attention to our needs, then we are gonna act on our own needs and create our own public spaces. So there was a boom of these spaces popping up all over the city in abandoned, again, abandoned lots or plots of land. Like you see here, this is… It’s hard to find words for these type of spaces. I get… In Spanish, sometimes they’re called… Would roughly translate to independent self-manage social space or cultural space. These spaces often had urban gardens and were managed openly, voluntarily by people in the neighborhood.

0:23:40.9 Megan Saltzman: And yeah, they were open. So anybody can come in and help or take food or other resources if necessary. Here’s another example. This sign reads more peppers and less cement. Again, referring to the ongoing gentrification, there was one group I was able to participate in on several occasions called fem placa, which means we make the plaza. And here in Catalan it says, we recover public space as a place of coexistence. And their goal was to intervene in certain plazas where there was mass tourism and where a lot of buildings had been torn down and simply carry out everyday activities. Really simple activities like just standing there or just standing and talking or being together as a group, maybe eating, maybe drinking something, singing or dancing or talking about history. There was always one historian at these events who would read the history, the disappeared history of these plazas.

0:24:57.0 Megan Saltzman: And one day every month there would be one of these fem placa interventions and they carried out these activities without getting permission. So technically what they were doing legislatively is not legal. The police did approach at least twice when I was there and they asked what was going on and then walked away. There is this other element of which perhaps you all have thought about in your classes where, when the resistance looks cool, it can be so to say… So to speak, approved or co-opted by the ciudad concebida. So for example, this could be something that could actually attract more gentrifiers or more gentrification projects. I had another example up here where there were these critical spaces that I was seeing a lot in 2005, 2006 in Spanish, they’re called medianeras, where the buildings have been cut in half and you can see all of their interior private spaces just exposed to the public, to the passerby, people who are walking by. And on one hand, these are very historically triggering, right? You see this and your history questions are immediately mobilized. What happened here? Something happened here in the past. And I also came across some kind of artistic installation, something similar. They had replaced the sink and a shower head and what other bathroom features in this medianera. And then the next year I came across a postcard of this same artistic installation.

0:26:51.6 Megan Saltzman: So there is this tricky line of where does the critical art begin or where does the authorities end up creating it or co-opting it into something that can be commodified or sold. So yeah, here’s another example of the fem placa group. And one of the things they did in one of these interventions was to count all of the private seats in a plaza versus public seats. For example, this is… In this plaza, 61% of the places where you could sit were private. They were mostly cafes and restaurants. So they were highlighting this problem of the privatization of a public space. If I have time, I can go through more of the ways that these self-managed public spaces were operating. Yeah, I can go into that later if we have more time. How they were operating and how they were sharing their resources. Okay, and then the last chapter deals with immigration. Spanish cities not only experienced a boom of gentrification in the ’90s and the early 2000s, but also an immigration boom. So there’s the crux or intersection of these two major social phenomena. And Barcelona has been the Spanish city with the largest population of foreigners and undocumented people. So contrary to the dominant discourses on immigration, which tends to reduce immigrants to numbers or often negative narratives, this chapter seeks to understand these realities more holistically and with eyes on the creative spatial agency of this group of people.

0:28:42.8 Megan Saltzman: And for this chapter, I mainly analyzed two documentaries, Si Nos Dejan by Ana Torres and Raval, Raval by Antoni Verdaguer. And I also include my own ethnographic research on the phenomenon of informal street vending. And so from these resources, from these sources, sorry, I was able to get a better understanding of barriers in public space, specifically physical barriers, racial barriers, and legislative barriers. And also, I was able to see a certain type of mobility, a frequent zigzagging mobile itineraries across Barcelona and also across from city to city transnationally. And I think this is important because we still have very dominant national frameworks for doing the type of research we do and the type of thinking we do about time and space. In these documentaries and in the research, Barcelona is not this glamorous location, but simply a labor stopover within a network of European cities, especially downtowns, centers of these European cities that increasingly need and depend on cheap multilingual service labor, but they don’t offer ways to do so legally or humanely with housing. So that was another conclusion I got from this research. And then also through these films, the ethnographic research, I also saw a lot of solidarity and what I call neighborhood citizenship, referring to social bonds between strangers at the neighborhood level within a dense heterogeneous urban space.

0:30:36.5 Megan Saltzman: And this might be something more Mediterranean. I’m not certain because I’ve primarily done research in Spanish cities, but yeah, within the density of compactness of the Barcelona city, I was seeing this neighborhood citizenship, which was facilitating a more accessible and flexible notion of belonging and upholding networks of care. Again, although temporary and in the face of both gentrification and deportation, and I should add that everything that I have shown you, all of these small resistances, all of these here… Oh, with the exception of this one, they don’t exist anymore. So these urban gardens, these are all new buildings now. Fem placa does not practice anymore. This one, it’s called Germanetes, it does still continue. It was able to secure some legal and financial support from the city hall, which has allowed it to continue. Also this volleyball court, these are all apartment buildings now. That is a reality of this type of small resistance that I’m talking about. I have a lot of other images I could talk about, but this past January, I was able to share my book in Barcelona. And again, the issue of housing was very visible. Here you can see like this means, in Catalan, tourist flat. So you could see the type of graffiti. Also another example of this ephemeral resistance. Okay. So I guess I will end there. And if there’s certain questions, I can show you more of the images that I have. So that’s all for now.

0:32:33.9 Julian Agyeman: Well, thank you very much, Megan. This is a fascinating presentation. And we’ve got several questions, but I wanna open it up because I remember in the early days when we were talking about this, you said, but I’m from cultural studies. You people are in urban planning. It doesn’t matter. What you’re describing here is what we call pop-up urbanism. The small practices of everyday urbanism, pop-up urbanism, and it can be anything from a mural to seed bombing, like throwing seeds over a piece of vacant land. So this is exactly in our domain. And what’s quite refreshing actually is to hear a non-urban planner coming from a different discipline, obviously talking about this. So with that said, we’ve got a lot of questions and I’ve got a lot of questions of my own because I know a lot of people at the Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice, and they’ve been doing some fantastic work. Isabelle Anguelovski and her team. I don’t know whether you got to meet them, but Marvin says, I thought Barcelona is a walkable city and a sterling urban community model.

0:33:46.8 Megan Saltzman: Okay. Yeah, thank you, Marvin, for your comment/question. Yeah, so that is definitely part of the image and reputation that Barcelona has, especially around the… In the 1990s with the Olympics and right after the Olympics, there was the creation of… Or maybe not the creation, but there was this concept called the Barcelona model. And I think it’s quite well known in architectural studies of like you say, a city that has prioritized its inhabitants, walkability, democracy, green spaces. But upon researching this, that it wasn’t fully true and that all that I described at the beginning of the presentation about… Sorry, I had to turn something off. About the neoliberal effects and the population of the downtown decreasing and it becoming an increasingly exclusive city, at least economically, that those were aspects that were not included in this Barcelona model. So yeah, I mean there are definitely positive aspects and realities and truths in that Barcelona model. And Barcelona has many positive aspects today as well, especially if you compare it to other cities. But when you speak to the locals, when you speak to those who don’t have much of a voice, like people who are being pushed to the periphery or who are outside the institutions, then you do see that it’s much more nuanced and that a large, perhaps even the majority of the population has been excluded from the decision making process in terms of urban planning in the last couple of decades.

0:35:36.1 Julian Agyeman: Great, thanks, Megan. We have a question from Shmuel who says, I’m a social activist from Israel and I have a question how authorities of Barcelona are trying to ensure accessibility of poor and low socioeconomic groups of the local population to public spaces in the city?

0:35:53.3 Megan Saltzman: Thank you for your question and comment there. It’s a little tricky to respond to this question because it also depends a lot on what political party is in the city council. So from around 2008 to 2015, there was political party that came from a lot of the protests. If you all recall, Occupy Wall Street in Spain, this was much larger, it was called the 15-M or quince-m. And this… It was a massive grassroots movement all across the country, especially in cities. And one of these leaders of that movement became the first woman mayor, Ada Colau. And so under her mayorship, there were a lot of initiatives taken in the city to try to make sure, for example, that poor, what you name here, poor and low social economic groups and also people with disabilities or mobility issues, elderly people, women. There was a long list of different demographics that they tried to include in the decision making process and also in the material construction and renovation of the city. In the last couple of years there has been less of that. But there are the basics, I don’t know the words for them, but like different textures on the sidewalks for blind people or different sounds for… You’ll have to help me with these words. The different sounds of like for when to cross the street and stuff for blind people. But that’s as much as I can say about that, that it really depended on who was… What political party was in the seat of the city council at the time.

0:37:48.9 Julian Agyeman: Thanks. Sticking with that, the city council idea, we’ve got a question and it’s two part. Is there a way that the spatial tactics of a ciudad practicada can be institutionalized or does that stultify or co-opt the nature of the organic cultural movement? And then second, how did the government of Ada Colau, she’s a socialist, and the Guanyem movement push back against or follow neoliberal policies?

0:38:16.8 Megan Saltzman: Yeah, Mika, thank you for this question. And I talk about this in my book. In my book I say that a lot of these spatial tactics, if you look at… If you say you look at 20 of them, you’re going to see a pattern which is that they’re responding to something that could be some kind of need and these needs could be picked up by the city council. Perhaps we need more exercise equipment in the city, or perhaps we need a volleyball court in the, sorry, in the city. Or perhaps we need more benches if everybody is sitting wherever. So that is something that could be picked up and in some cases it has been picked up and worked on. However, as I mentioned in the book, the creativity, human or mammal creativity of spatial tactics, of being able to constantly adapt and re-adapt, it would continue. So I think that even if the city council did pick up on these and try to improve them, or if they picked up on them and improved them and then commodified them, which I could talk about some examples where that has happened, especially in terms of sustainability and green initiatives.

0:39:31.4 Megan Saltzman: Either way, at the grassroots level, there will continue to be this creativity of circumventing whatever is there or whatever is not there. Let me see the second part of the question. Yeah, that’s a very big question about how the Ada Colau government pushed back because they did so many things. I can send you my book chapter if you like. So many things. I suppose the initiative that they were most internationally famous for is what’s been called… I’ll put it in the chat, it’s in Catalan or I think in English, they’ve been called translated to superblocks. And that is where they take a group of nine blocks and they make all the streets within those blocks for only pedestrians. And their political party, Barcelona en Comú, they created several of these super block conglomerations across the city of Barcelona. And yeah, you can see online on one hand they have become more sustainable, greener areas and for the most part they’re used. You can see people walking around, sitting, playing a wide variety of activities. On the other hand there have been complaints because there is always that population that wants to drive or that want to take their motorcycle.

0:40:56.9 Megan Saltzman: And so this pushes traffic and creates traffic jams in other parts of the city or pushes the pollution to other streets. And perhaps the unintentional effect of these superblocks was that the housing around the superblocks skyrocketed. So now everybody wants to live on a superblock and it has ended up pushing out lower and middle income residents. And yeah, this is in the news like right now, the last couple of weeks there’s been all the… A lot of talks and protest about the housing in these neighborhoods. Let me go back to your question. Where there… Where do there… Supposedly people find the policy, on the spectrum. Yeah, you had written about the superblocks. Well, the superblocks does fall on the spectrum. The progressive political party or if you wanna call it the left wing or whatever, but it fell within the spectrum or the part of the party that’s called Barcelona en Comú and there’s a lot of other examples of trying to… In Spanish they use the word pacificar which is like to make pleasant or to make peaceful, the public spaces for more pedestrians and areas where no cars would be allowed.

0:42:17.7 Megan Saltzman: For example, they also, on Sundays they have blocked off a lot of streets where cars can’t go through. They have also, you might have heard of something called bicibús, which is… If you Google it or look on YouTube you can see videos of it. They in the morning and in the afternoon when kids are going to school and when they’re coming home from school, they’re blocking off certain streets where all the kids can go together on their bikes. So that was another project. They also did try to… I have this chapter about these kind of independent public spaces/cultural centers. They did try to financially support several of them but again it was… It would be… It’s also temporary. It would be like financial support or permission for one year or two years and then when that party gets voted out, then they lose their support. It’s a big question. If you email me, I’ll send you my chapter and then you can get more of the specifics.

0:43:25.0 Julian Agyeman: Thanks Megan, for that. I’m going to ask a question of my own. Those of us in the sort of sustainable communities, sustainable urban planning field, Barcelona is often held up as being one of the key models. What do you think we should take from that? And what should we not take from Barcelona as being held up as one of these models? A socialist mayor, the superblocks, action on Airbnb, tourists go home, refugees welcome. This is a heady mix of progressive policies. What do we take and what do we leave?

0:44:01.0 Megan Saltzman: Yeah, yeah, that’s a good question. Well, I think you have to be constantly critical and you have to… In the book I talk about what happens when we start comparing cities and when we start to compare cities, like, oh, well, Barcelona is so much better than Philadelphia or for example, then we are disregarding the suffering that’s going down in Barcelona, for example, or we are ignoring the people who are not being included in these decision making or these initiatives or projects. So I would say sure, take the good, take the positive from whatever model and also whatever non-model and also take a nuanced view. What’s being left out, who’s not being included in this and ask a lot of questions. In the research for this book, it was just all about asking questions and asking questions. I’m not from Barcelona. I spent a long time living there. But I needed to ask questions not from just institutional people, but from absolutely anybody who is willing to speak with me. So, yeah, sure, again, take the positives, take the good parts, but also be critical. Know that there’s most likely something that’s not being talked about or most likely somebody who’s not being included. Yeah, yeah, just take a more nuanced view of… Yeah, I don’t doubt that Barcelona has positive things that I wish we could incorporate and repeat in Boston or elsewhere, but you have to get as holistic a view as possible of what that model…

0:45:38.8 Julian Agyeman: Another good example, Amsterdam and Barcelona are two of the only cities with sort of protection of people’s digital rights on the Internet. Some very progressive things coming out of Barcelona in that sense. Final question, and this is a real quick one and hopefully you can answer it pretty quickly. Would you be able to talk any more about those examples you referred to where cultural and social spatial practices have been commodified and the results? So just give us one example, maybe.

0:46:09.2 Megan Saltzman: Have been commodified and the results. Oh, probably one of the most popular ones, which I think is not getting so much attention nowadays, but about 15 years ago was the Barcelona graffiti. If you again put into Google images Barcelona Graffiti, you’ll see a massive database of very creative graffiti examples from all over the city. And this really increase tourism to the city. And so this was something also that the city council promoted as this… Barcelona as the city of creativity, the city of art, of informal art. And I would say probably something like 90% of those graffiti artworks are gone because they have destroyed the buildings to create new hotels and new tourist apartments. And I would say right now the biggest case is what’s going on with the superblocks.

0:47:08.8 Julian Agyeman: Great, Megan. I could ask many more questions and there’s many more questions just keep coming up in the chat. But what a fitting end to this semester of Cities@Tufts. Megan Saltzman, Mount Holyoke thank you so much. Can we give a warm round of applause, a warm Cities@Tufts round of applause to Megan Saltzman. Thank you Megan. Thank you so much. As I said, this is the last for this semester. Hope to see many of you back in September for a whole new raft of fantastic presentations.

0:47:41.2 Tom Llewellyn: We hope you enjoyed this week’s presentation. Click the link in the show notes to access the video, transcript and graphic recording or to register for an upcoming lecture. Cities@Tufts is produced by the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University and Shareable, with support from the Barr foundation, Shareable donors and listeners like you. Lectures are moderated by Professor Julian Agyeman and organized in partnership with research assistants Amelia Morton and Grant Perry. Light Without Dark by Cultivate Beats is our theme song and the graphic recording was created by Jess Milner. Paige Kelly is our co-producer, audio editor and communications manager. Additional operations, funding, marketing and outreach support are provided by Alison Huff, Bobby Jones and Candice Spivey. And the series is co-produced and presented by me, Tom Llewellyn. Please hit subscribe, leave a rating or review wherever you get your podcasts and share with others so this knowledge will reach people outside of our collective bubbles. That’s it for this week’s show.