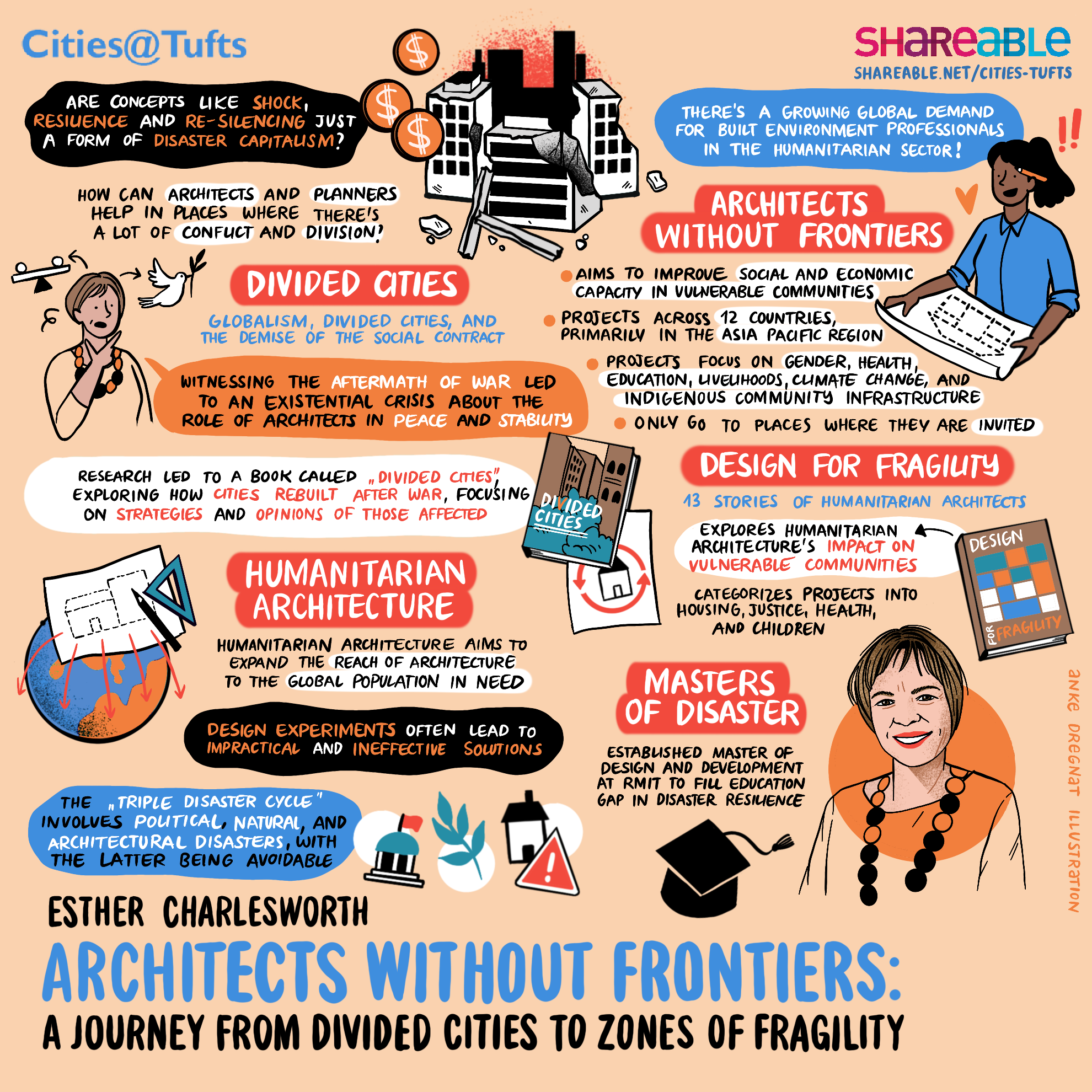

Prof. Esther Charlesworth’s talk focused on her nomadic design journey across the last three decades. In trying to move from just theorizing about disaster architecture to designing and delivering projects for at-risk communities globally, Esther started both Architects Without Frontiers (Australia) and ASF (International); an umbrella coalition of 41 other architect groups across Europe, Asia and Africa. Architects Without Frontiers asks, how do we go from just pontificating about the multiple and intractable challenges of our fragile planet, to actually acting on them?

About the speaker

Professor Esther Charlesworth works in the School of Architecture and Design at RMIT University, where in 2016 she founded the Master of Disaster, Design, and Development degree [MoDDD] and the Humanitarian Architecture Research Bureau [HARB]. MoDDD is one of the few degrees globally, enabling mid-career designers to transition their careers into the international development, disaster and urban resilience sectors.

Transcript

[music]

0:00:08.3 Esther Charlesworth: Why are the disasters of our time, war, extreme poverty, sea level rise, relevant to design? I argue because if we distance our spatial practices from the big global challenges of our time with the line, “I’m just an architect,” “I’m just an urban planner,” “I’m just a landscape architect,” we become part of the problem. Deep ethical agency in design reaches a point of saying, “I want this to come into the world and will bring this about.”

0:00:38.6 Tom Llewellyn: Welcome to another episode of Cities@Tufts Lectures where we explore the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities designed for greater equity and justice. This season is brought to you by Shareable and the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University with support from the Barr Foundation. In addition to this podcast, the video, transcript, and graphic recordings are available on our website, shareable.net. Just click the link in the show notes. And now, here’s the host of Cities@Tufts, Professor Julian Agyeman.

0:01:12.0 Julian Agyeman: Welcome to our joint Cities@Tufts Boston Urban Salon hybrid colloquium. This is a first for us. I’m Professor Julian Agyeman, and together with my research assistants, Deandra Boyle and Grant Perry, and our partners, Shareable and the Barr Foundation, we organize Cities@Tufts as a cross-disciplinary academic initiative which recognizes Tufts University as a leader in urban studies, urban planning, and sustainability issues. Boston Urban Salon is an urban seminar series co-organized by urban experts from different Boston universities and colleges, and we have representatives here from Harvard, Northeastern, from Boston University, and myself from Tufts as members of the Boston Urban Salon seminar committee. We’d like to acknowledge that we’re on the Medford Campus of Tufts University, which is located on colonized Wampanoag and Massachusetts territory. Tonight, we’re delighted to host Professor Esther Charlesworth.

0:02:13.5 Julian Agyeman: She’s a professor in the School of Architecture and Design at RMIT University, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, where she founded the Master of Disaster Design and Development degree. She’s also the Founding Director of Architects Without Frontiers and also one of the founders of Architecture Sans Frontières International. She’s worked in the public and private sectors in architecture and urban design in Melbourne, Sydney, New York, Boston, and Beirut since graduating with a master’s in Architecture and Urban Design from Harvard in 1995. In 2004, she was awarded her PhD from the University of York in England, and she’s published eight books on the theme of social justice and architecture, including, Divided Cities, 2011, Humanitarian Architecture, 2014, Sustainable Housing Reconstruction, 2015, and Design for Fragility, 2022. Esther’s talk today is Architects Without Frontiers; A Journey from Divided Cities to Zones of Fragility.

0:03:19.6 Esther Charlesworth: Thank you, and I’ll say g’day for those who know where I come from.

0:03:27.3 Speaker 4: It’s undeniable that poverty, conflict, social marginalization, and climate change are all powerful forces affecting people’s lives in the world today. Whilst there’s many responses to such challenges, architects and designers are uniquely equipped to assist those affected through seeing design, not just as a product, but as a process. For more than a decade, Architects Without Frontiers has been designing and delivering health and education projects that radically improve the social and physical infrastructure of vulnerable communities right across the Asia Pacific region. We design with local communities to create solutions that are environmentally sustainable and closely integrated with the culture of the region.

0:04:20.5 Speaker 4: We combine local knowledge, local materials, and local building techniques to create long-term projects that are owned by the people and communities they benefit, projects that produce much more than just a roof overhead as they help to rebuild lives and livelihoods. As a key player in the global design and development community, we’ve proven that good design can have a huge impact on the effectiveness, value for money and lifespan of development projects. Since 2005, Architects Without Frontiers has worked with the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Red Cross, the City of Melbourne, RMIT University, Arup, the Planet Wheeler Foundation, and other prominent Australian organizations. Between them, we have delivered 39 health and education projects in 14 countries across the globe.

0:05:19.3 Speaker 4: We’ve partnered with 60 architects in delivering pro bono design services while collaborating with 70 communities to improve their social and physical infrastructure. We have also trained over 80 Australian architects and project managers to work in the humanitarian sector. Whether it’s a financial supporter, individual architect, or large design firm applying their expertise, our members are united by the desire to contribute their skills, time, and resources to working with communities that can’t normally afford to pay for design themselves. By the year 2020, our vision is to make innovative design accessible to vulnerable communities globally. We also hope to mobilize 100 Australian design and development professionals to work with us and to deliver another 50 health and education projects for those who need them most. We need your involvement now to help transform lives through design.

0:06:23.6 Esther Charlesworth: So thank you to Julian for the invitation. And it’s really a strategic moment to reflect on my long journey that actually began here in Boston from Divided Cities to Architects Without Frontiers, which has led me to believe that architecture and planning can indeed have few frontiers, but perhaps greater moral agency in dealing with disaster, war, poverty, food and water security, indigenous sovereignty, and sea level rise. But how do we bridge the insidious gap between the 95% or 98% of the global population, I would argue, who are in most need of design, but who have least access to it? Tonight, I’ll be walking through these five platforms and I hope to offer a roadmap beyond the jargon and the cascading crises towards stories of hope where architects, urban planners, and landscape architects have addressed and often transcended the big challenges of our time, from Alabama to Afghanistan through what I call as their tools of spatial diplomacy.

0:07:31.5 Esther Charlesworth: But before I begin on these five platforms, I’m just going to sort of put up four questions or provocations up there. So in design and planning, I guess we’re all talking about these words, shock, resilience, resilencing, and the tools to deal with them from building back better to the SDGs. And in many ways, they’re the topics du jour, but might they merely translate as another form of disaster capitalism, as Western White bourgeois and colonialist sentiments. And for example, as one critic has noted, that the real post Hurricane Katrina story is not a story of resilience at all, but has been rather celebration of disavowal and resilencing. Onto the second question, the cult of the trauma glam architect. So here we have what we call in Australia, FIFO, fly in, fly out. There is a modality amongst architects who fly in, Norman, Sir Lord Norman Foster, sorry, I gotta get the acronyms right there, wouldn’t wanna offend anyone, was known to, he’s got his own private plane, flew into Kharkiv three years ago and said, “We will rebuild.”

0:08:48.0 Esther Charlesworth: However, it’s all very reminiscent of what happened after the Marshall Plan after World War II, and in fact, the zeal to rebuild at no cost in a way like Cobbs v Regio scheme. But I’ll be coming back to Norman and this cult of the trauma glam later in my talk. Now, the next point is that we are simply deluged by data and so-called wicked problems, the analysis, the paralysis, the data overload. We all know the problems, the poor, sad, homeless bears, submerged Venice, the couple just trying to get married in the ruin of their city, Aleppo, and to the threat of our AI, where one colleague has said to me that probably 50% of architecture and design jobs will be gone in the next three years. And all of these challenges might in fact overwhelm us to act. And Peter Singer calls, an Australian philosopher, calls this the diffusion of responsibility. That is, that the more people affected by a scenario, in fact, the less likely we are to act. And I’ll be coming back to this later on.

0:10:01.7 Esther Charlesworth: Are you already depressed? There are some good stories at the end, so please hang on. So tonight, I’m gonna take you through these five platforms, Divided Cities, where my journey first began, Humanitarian Architecture and the strong demand now for architecture, urban planners and landscape architects beyond mainstream practice models, Architects Without Frontiers, which is now the largest design, not-for-profit in the Asia Pacific region, Designed for Fragility, my last book, and the Master of Disaster Design and Development. And because there are students in the audience, really what that degree has been about. But moving on to Divided Cities. So nearly three decades ago, while studying at the GSD, I had an internship lined up at IM Pei’s office in New York, and I thought I was headed for the pyramid structure of architecturaldom. And somebody said, “Look, the Aga Khan program at MIT is needing volunteers to go to Mostar this summer, would you be interested?” I really didn’t know much about the Balkan Wars, I definitely didn’t know where Mostar was.

0:11:08.7 Esther Charlesworth: However, I ended up there that summer as part of an international team of architects working on the reconstruction of the city after the Balkan Wars. The famous Neretva River, Mostar had this fantastic diving competition. It was very much this city that was a bridge between East and West until it got shattered in 1993. This all for me created a kind of existential crisis. Surely architects are involved in peace and stability and what lawyers and logisticians do, we seem to, as a field, blow up buildings in the late 1970s, we captivated by postmodernism and structuralism in the late ’80s and the ’90s were, we were immersed in deconstruction, not war. That was somebody… Not peace, not rebuilding, that was somebody else’s business. What I was seeing while we were doing our fancy design schemes on Yellowtrace was the local people had no roof overhead, no running water, and no electricity, while we were coming in with our sort of fancy schemes about where we would rebuild and how, and really focusing on the architectonic nature of the problem.

0:12:21.5 Esther Charlesworth: That all then led to a 10-year project and a book, Divided Cities, that was funded by the MacArthur Foundation. And how that came about is that after the Mostar experience, myself and a colleague from Columbia, really came to understand what other cities had done after war. How they had rebuilt, through what strategies and what were the opinions of people from the snipers in Beirut to people who’d been leading the reconstruction about that. So that’s a journey that was really enabled as I said, by that MacArthur grant. Also led me to, I went to Beirut for three months and I ended up there for three years, which is the story of my life. I go somewhere for a month and then I’m there for a decade. So is anyone familiar with Beirut here? So you might know of the scheme to rebuild Beirut, which is basically, this is the downtown area. It was a laissez sort of urban planning scheme funded by the former Prime Minister of Lebanon, Rafic Hariri.

0:13:26.1 Esther Charlesworth: But what was the problem, apartments on the right say cost about a million American dollars. This is two decades ago. On the left is an image of what Beirut was like before the war, but the average income of a Lebanese person is $10,000 US a year. So there’s this huge discrepancy about designing and planning for people of the super elite that I guess we’re still dealing with. All of this reminded of a no man’s land, a continuum of urban segregation, so that we could never see 20 years ago the number of walls that have been erected since. And that in fact, all cities could be sort of somehow plotted on this line between urban’s perfect integration and perfect segregation, if that, and beacons of a larger urban class. And in fact, two years after our book, we see the separation wall dividing parts of Jerusalem’s Eastern Palestinian towns from the old town of Jerusalem or on the bottom slide there, the Great Wall of Calais, locking out Libyan asylum seekers who’ve arrived by boats.

0:14:36.1 Esther Charlesworth: So these walls, I mean, they’re everywhere and we could have added 80 more cities now onto our Divided Cities project, but that just got us started. Onto the next platform, humanitarian architecture. So humanitarian architecture, I argue, is not an antithesis to traditional design practice. Rather, it serves to broaden architecture’s public reach to the global 90%, who I said at the start of my talk, who are in the most critical need of design, but who have generally least access to it. However, it’s far from always been a noble cause where tragic events are awfully swiftly turned into design experiments. So on the right is a project done by the Future Shack, a very well-known Melbourne architect called Sean Godsell. Sean seriously thought that 40,000 of these units would be put up by the UNHCR. The problem is they had no fire retardant. They were destined for Sri Lanka, where they would have fallen apart. It was so successful, it had its own exhibition at MoMA, but not one Future Shack was actually ever built because it was a disaster. It was a utopia.

0:15:45.9 Esther Charlesworth: On the left, Renzo Piano’s scheme, again for Sri Lanka, would have just imploded by the time it got to Sri Lanka with the human condition. We could do a whole lecture on design experiments, but I won’t. Just give me a bit of time. So you all know the Make It Right housing in New Orleans that then Jolie-Pitt Foundation got up. Again, most of this housing was built two years too late, triple the cost, and for example, totally inappropriate. The red house on the left was for a disabled couple. The disasters continue from what I saw in Port-au-Prince. On the top left, an igloo scheme designed for housing by an American building company wanting to get into the business of disaster. It was 42 degrees inside, and in fact, the only people they put in there were the Haitian Red Cross staff. On the bottom left, a beautiful image. It’s almost like a kind of a Mondrian painting. However, this is where they parked 300,000 residents with no running water, no electricity, and no access to their place of work. And the best scheme of all is in Christmas Island in Australia.

0:16:54.7 Esther Charlesworth: This is a motel where we like to put our refugees, asylum seekers on boats in Australia. I won’t go there, but this is a scheme done by an architect, which is obscene. So it’s a cliff. It’s somehow where the poor asylum seekers land and then get jettisoned off. All of this leads to what I call the triple disaster cycle, where we have the political disaster that we saw in Beirut, Haiti, Sri Lanka, preceding the natural or the unnatural disaster of the cyclone, the tsunami. But the architectural disaster is the one that could be avoided, and that is the whole issue here. This all then led me to doing this book to try to locate these architects I was finding along my pathway who weren’t just doing this as isolated projects, they were actually making a living out of it. And some of them you know, Michael Murphy, Shigeru Ban, and the late Paul Pholeros. And also what this book was about, that these aren’t sort of… Humanitarian architecture is not something that you do when you’re looking for a day job.

0:18:06.1 Esther Charlesworth: You’re not sitting underneath a tree in Africa singing Kumbaya and it’s all furry and green, that’s what it’s about. No, there is a global demand for built environment professionals in the humanitarian sector right now, and I’ll come back to that at the end of my talk. Now, here we see, this is from Shigeru Ban’s own book on humanitarian architecture. Aren’t they beautiful images? Housing in Onagawa after the Great East Japan earthquake. So again, the FIFO architect, fly in, fly out, came in a helicopter, I was told by the residents, I haven’t verified it, got out the Yellowtrace, said, how’s it going? So I’ve seen time and time again the fancy photographs, but actually what hits the ground is something far more tragic and inappropriate. Now, most of you would have heard of the MASS Design Group here, hands up. Those who haven’t, they’re sort of a legendary architects who came out of the GSD, and I’m not going to talk about their work so much as their model of practice, as it was originally set up by the two founders.

0:19:12.9 Esther Charlesworth: In that, there were four quadrants, design, research, training, and advocacy, so that the for-profit work could underwrite the pro bono work, because that’s the problem. If you get too involved in pro bono work, as what’s happened with Architects Without Frontiers, it’s not sustainable financially. So now onto my own practice. And after 30 years, or no, probably 20 years by this stage of theorizing about architects’ roles after conflict, doing my PhD, I felt it was time to sort of build on all that theory, and how could I make this happen? I hadn’t met any architects working in this field, I’d met an engineer working for RedR, Engineers for Relief. The mission of AWF is to improve the social and economic capacity of vulnerable communities through the design and construction of health and education projects. In fact, this is updated since the last video, but we’ve now completed about 70 projects across 12 countries.

0:20:16.3 Esther Charlesworth: While I’d like to say our remit is the Asia Pacific region, we’ve done a lot of projects in East Africa and as far away as Afghanistan and Belize and a lot of projects in Australia. Now, the important thing is how are we funded. All of these things are great ideas, but we know from Architecture For Humanity went down with something like $3 million in debt. Emergency Architects in Australia, the great ideas, but how do you fund them? So we have 12 corporate donors, six of the top architecture firms in the country, engineers, a quantity surveyor who each fund us with $20,000 a year, which underwrites two paid staff. That’s how the work is done. And then those organizations give their time for free to schematic design. And we believe that in any project, we generally need the services of an architect, a landscape architect. And if we can’t cost it with a quantity surveyor, then it’s not good. We are not fundraisers, people come to us with a project they’ve already got the funds.

0:21:21.4 Esther Charlesworth: We have three main impacts, gender, health, education and livelihoods, climate change and building of resilience and indigenous community structure. And I’ll be talking about some of the projects up there and three main programs of activity, design, build, training and education. One of the first projects we did is in Ahmedabad, in a slum there, building these [inaudible] out of refuse material. Australian volunteers go for six months and before this, the kids, preschool kids just, there was nowhere to go. Now, when I returned to Australia after being in Beirut, RMIT is the largest foreign university in Vietnam. I was sick and tired as both a student or as a staff member. I’ve taken students into vulnerable communities in a design studio, and this year we’ll go to Ecuador. Next year, we’ll go to Belfast. Next year, we’ll go to Sri Lanka with the promise that we were gonna do something, but nothing actually got delivered. So when I went to Vietnam, I really took three years. There’s a lot of Australian not-for-profits working there to sort of understand what we could do.

0:22:32.5 Esther Charlesworth: And then I led this studio, building the community studio and architects, landscape architects, multimedia and design students from RMIT Vietnam in HộI An in Vietnam, between Ho Chi Min City in the South and Hanoi in the North. Some of the student sketches, but then it got built. Somebody very senior in the organization when I ran a workshop pulled me aside and said, “Esther, how much would it actually cost to build this project?” I’d had it funded, said about $250,000 US. And he said, “I’ve got that surplus in my budget.” And I was like, crikey, ’cause this wasn’t a capital works project. So I quickly got the deeds drawn up before somebody changed their minds and this project was built. What this project is about, this area of HộI An has the largest incidence of Agent Orange after the American Vietnam War of the rest of Vietnam. So there’s an incredible amount of physical and intellectual disability in generations of families. So kids like here have no future. They’re in the kitchen or they’re in the bathroom. They have no future for education.

0:23:44.7 Esther Charlesworth: So what this is about is not just the building, which was a simple vernacular building. The materials were procured by the people’s party in Da Nang, is that it gave 100 kids, 120 kids there now who go a life back and opportunities, but it meant that a parent could go back to work and a grandparent. So it’s had an impact on more like about 3000 people. So I guess AWF is about rebuilding the hardware of the building, but also the software of people’s livelihoods that’s critical. In the same line after the Boxing Day tsunami, we were asked to do by the mayor of Galle, two mobile libraries in Galle and Hambantota. We bought two Leyland Lanka buses, fitted them out and they hit the ground. Again, not fancy buses, but there was no internet, people had no access to reading in their villages or no news. It was about employing the driver, the assistant driver, the librarian, and the assistant librarian that really mattered on these projects. One of the biggest projects we’ve done that represents this design brokerage model is a women’s cultural and social enterprise hub for our department of Homelands or our Department of Foreign Affairs.

0:25:00.9 Esther Charlesworth: This area of Fiji has the largest incidence of domestic violence in the South Pacific. So people won’t go to police stations to report this. And this is for women who come from all of the remaining Islands to both share their stories but also to trade craft. So this is a view, not too shabby. On the top is an image, obviously it was modeled on the traditional bure in Fiji, nothing fancy. What’s more striking about this project is that 58 business development courses have been run for women there that has enabled them to gain a livelihood. So again, it’s just not about the building, it’s about the livelihoods that come about throughout that, that perhaps far more lasting. We’re now doing the second stage of that project, the information hub. I’m gonna show a few other projects, Maningrida, right up at the top end where we’ve done an arts and culture precinct. Now, to give you an idea, who in the room has been to Australia? Some of you need to get traveling, please. Diane, Loretta, come on, we gotta get you Down Under.

0:26:07.2 Esther Charlesworth: So to give you an idea, I live down here in, this is about the same land mass as North America, from East to West. Maningrida is where I’ve been working, the top end. The closest city is Denpasar, where you would fly into if you want to go to Bali or Indonesia. This is a map of indigenous groups and languages in Australia, so just to show the complexity. In this area, I could go from Melbourne to Paris, it would take me the same time as going to Melbourne to Maningrida, seriously. Very interesting group of twin 12 multi-language or skin groups that we worked on this arts and culture precinct with. And generally, this is what we do. Pull together a schematic design, get it funded and hand it back to the client. The Northern Territory government now is looking at funding this project. This area is also very famous for rock art. Now, a project we’re doing right now is in Ramingining, just to the East of where I showed. Now, indigenous housing in Australia, remote indigenous housing is a disaster, and I’ll quickly tell you why and I am getting to the end of my talk.

0:27:21.1 Esther Charlesworth: Now, these are the kind of landscapes in Australia. For most of our middle, there’s no Wyoming, there’s no Minnesota, there’s nothing. Remote indigenous housing provided by the government is a spectacular disaster because it’s framed on the nuclear family model, that there is a mum, dad, and two or three kids. In fact, there is not a nuclear family in remote indigenous kinship structures. Generally, the grandmother will bring up the kids and there are a lot of avoidance issues when it comes to designer housing. So the one house fits all is generally a disaster, but what it keeps being built. And then these images appear in the news and then people say, “Oh, these people can’t look after their houses.” They’re built by crook contractors, the slabs are laid really badly. I probably wouldn’t live there either and probably bash up my wall as well. A house is not a home there. It can be a place for storage as we know in a Western way. And then this is just a bit of a sad image of what is currently being produced on the right.

0:28:28.9 Esther Charlesworth: Now, this is, again, to the East of where I was talking about where I’ll be in a couple of weeks time in Ramingining, where we’ve been asked to do a pilot indigenous house that could be scaled up to 10 houses in the region. And what we’ve been looking at is design exemplars. What are light, off the ground? This is a coastal area. Most indigenous communities are living outside. This is the kind of environment that they want. So we’ll be visiting a lot of these exemplar projects to understand what are the best forms of housing because we’ve got a great client who’s also the donor for the project. Moving on, just to show the range of our project before I get to the end here, top end. But we’re also doing a series of domestic violence shelters for women two kilometers from where I live in Melbourne, in Preston. And no, there’s nothing very significant about a bunch of toilets, is there? Except before we got involved, 30 women and kids were sharing one bathroom. And through this project and through the funding, women got their dignity back together again.

0:29:37.4 Esther Charlesworth: They’re only in this transitional housing for two weeks. It is their right to have some dignity, to have a shower and their kids in peace. And this stuff mightn’t be award-winning, but it’s transformational. Afghanistan, an embroidery workshop and just in terms of some of the impacts of the project, a place where women learn textile skills to enable them to safely earn a living. What’s extraordinary about this project, it was built under the fall of the Taliban, and it was actually a women’s group who got it up. And I’m just gonna finish off here with some other projects we’re currently doing. Most of our projects are health and education, they’re not housing. Gambia, a cancer clinic there. So we are pulling together these schemes, getting them costed, handing them back to the client. And more recently, as you might know, the South Pacific, half the islands are very prone to sea level rise and a third of them are already underwater. So these are for climate change resilience centers that will be containers for disaster materials but also for training in terms of community resilience.

0:30:44.4 Esther Charlesworth: The land has already been found in Tonga and the first one of these will be built next year, another village relocation project. And just any of, before I sort of end up with the MAUD story, is to say disasters happen with Architects Without Frontiers as well. So this was a project that I felt was going really well. It was in Dar es Salaam outside Tanzania, a project for victims of sexual violence, teenage girls. However, the architect I think was thinking of the Apple headquarters in Cupertino when they came up with this remarkable scheme, which looked great and probably would’ve won an award in Architecture Australia. But the cost per square meter in Tanzania is $700 per square meter. This took it up to $8,000 a square meter. So we actually had to intervene. So occasionally we see totally inappropriate buildings like this that will just further promulgate the violence of already traumatized communities. Onto the second last, my book Design For Fragility, this tried to go a bit deeper than humanitarian architecture in terms of not only interviewing the 13 architects, but interviewing the beneficiaries of the projects.

0:32:00.0 Esther Charlesworth: What did they think? What did the local project manager think? What did the midwife think? To go a bit deeper. I’m just gonna show these are the architects. It was framed in four main typologies, housing, justice, health, and children. This is a project demand done by Urko Sanchez, and I guess most of these architects represent a sort of a Robinhood architect. Urko Sanchez is running a very fancy practice in Madrid doing houses in Majorca, but also on the Horn of Africa in Djibouti. And this is what the local project manager had to say about what the project meant for his part of the world, what it meant for them. Then a lot of the MASS design group. What was interesting about this project are the interviews that were undertaken with the midwives, their view that women were walking for two days to these rural villages, that this was saving lives. And you can’t often say that architecture saves lives, but this project did and has set a precedent for other healthcare centers in the region.

0:33:09.1 Esther Charlesworth: Anna Heringer, some of you might know. Again, spectacular building, it’s won an Arch-Con Award but Anna has also set up an NGO for the disabled women here who are creating textiles and who can gain a livelihood throughout that. The last project here is done by Local Works in Uganda. It was built with the migratory tribe people formerly known as the Pygmies and when their land was dispossessed by the forces of guerrilla tourism which is now a really big deal in that part of the world and it was declared a national park and all of these people were moved out. So what’s interesting about this project, it’s very simple but what I love, if you can see the aerial image here of the village, it’s actually a heart shape. And they’re actually twigs and sticks that the local women put around their village to protect their chickens from the marauding tigers outside. And so I think that was particularly beautiful. So the emerging themes of this book, and I guess getting towards the end here, the zones of fragility. Again, the increasing mandate for architects and built environment professionals to work in zones of fragility.

0:34:24.8 Esther Charlesworth: We see doctors, engineers, economists, lawyers at the forefront of addressing these sources of fragility but architects are largely missing in action. The rise and rise of humanitarian architecture. Despite the demand for architects and landscape architects to have skills in urban resilience, climate modelling, design thinking, where are the dedicated design programs? In the USA, throughout most of Asia, we’ve got one in Australia. They simply don’t exist. People will do a one-off studio but it’s not seen as core business. Poverty does not exclude aesthetics. Most of these projects won design awards. This is not a game of aesthetics, you can be doing both. Thirdly, if you don’t measure it, how much do you know? Architects aren’t great on how do we know what we know on doing post-occupancy evaluations, but four of these projects did. And the last point, trauma glam. Working in disasters has become the theme du jour for many architects with what I call deprivation irrelevance syndrome. And according to a psychiatrist friend of mine, it’s actually a real term.

0:35:34.8 Esther Charlesworth: As we were completing this book, again, Foster was in Ukraine to discuss the reconstruction of Kharkiv, proposing a master plan to be developed by the best minds in the world, best planning, architectural design and engineering skills in the world. And yet from Gaza to Kiev, these sites of despair, I argue, are not laboratories for design experiments. On to the final part of my talk and in wrapping up. So I set up the Master of Disaster Design and Development at RMIT because I felt in my journey there was nothing like this. We were doing these design studios, but there was nothing giving me the skills that I needed to do to work in this sector. We set up the course from scratch. It was the first online degree in the School of Architecture. It’s run, we have students from all around the world. We actually have three from America because there’s nowhere to go in the States to do this kind of degree, and they can enroll online. The 101 courses, design, disaster and development, shelter and settlement, and then students enroll in a number of electives from post-disaster project management, humanity architecture, communication for social change, etcetera, etcetera. Some of their voices before I wrap up.

[music]

0:36:57.2 Speaker 5: The Master of Disaster Design and Development is in some ways the encapsulation of the concerns that exist within the School of Architecture and Urban Design at RMIT.

0:37:12.4 Speaker 6: It had a long gestation, maybe four or five years, out of a lot of discussions through the International Federation of the Red Cross, RMIT Europe, the Australian Red Cross, World Vision. People across the world who are really interested in putting together a degree in the Asia-Pacific region to train the next generation of humanitarians.

0:37:33.8 Speaker 7: There are going to be increasing disasters around the world. The toll on humankind is going to be very great. If we have a group of people who already have some skills, from a bachelor’s degree, from service, in other disciplines, they bring a lot to a degree like this where you’re adding on a new component, dealing with disasters, both before, after, and during.

0:38:01.4 Speaker 6: As a graduate student, I had the incredible opportunity to get involved in a project to rebuild Mostar, and it really got me thinking about these issues and the capacity of design to deal with the complexity of social justice, the role of spatial thinking in dealing with these really complex issues of peace, war, disaster and division.

0:38:24.5 Speaker 8: I chose to do the MAUD degree as it was like a solidifying of almost of the experience that I’ve been on, of working out or developing that past experience in the humanitarian sector through study. During the time as an architect, I did a bit of work with Architects Without Frontiers. I’ve been across the board a number of times, been working in that sector a little bit, even though I was only through community development work, but I really wanted to get in there and study. When the MAUD degree came available, I was like, “Yeah, I’ve got to do this.” MAUD has enabled me to transition into the disaster relief sector by opening up of opportunities in terms of deployment by RedR as an expert on a mission to work with UNHCR in Nepal, undertaking site planning for consolidation of the remaining refugee settlements into a single refugee settlement and working with their temporary shelters to be more robust.

0:39:14.0 Speaker 7: MAUD is the only degree in the world that I know of that really is transformative. It doesn’t just give you a skill on how to build a building or how to work with people because they have trauma. It gives you those skills so you can manage all those disciplines and really bring to bear the kinds of skills necessary to run the entire operation, like a Katrina or after a tsunami. Not just to be there, not just to be a helper, but to help manage the thing to the future.

0:39:48.4 Speaker 6: MAUD is engaging, compelling.

0:39:53.4 Speaker 5: Eye-opening.

[music]

0:39:53.4 Esther Charlesworth: Just some final words. So 28 years or so after my first immersion into Mostar and Cities Divided by Conflict, why are the disasters of our time, war, extreme poverty, sea level rise relevant to design? I argue because if we distance our spatial practices from the big global challenges of our time, like we’ve done with project management or outsource ethics to others with a line, “I’m just an architect,” “I’m just an urban planner,” “I’m just a landscape architect,” we become part of the problem.

0:40:28.8 Esther Charlesworth: Deep ethical agency in design reaches a point of saying, “I want this to come into the world and will bring this about.” Bridging just pontificating about our fragile planet as we are very good at doing as academics and acting within it. A quote from my friend Erik Kessels, design remains the most powerful tool we have for confronting humanity’s most serious challenges. It has the potential to heal us from any past crises and ameliorate or fully eliminate the effects of forthcoming ones. Design is a Swiss army knife of cognition. So social infrastructure, what were the other words there? Human centered architecture.

0:41:15.7 Julian Agyeman: Yeah, yeah.

0:41:16.4 Esther Charlesworth: And infrastructure. Yeah, I think we are basically talking about exactly the same things, but perhaps with different words. That it is very much about the words you’re using, human centered architecture and infrastructure. And the only difference I would say is if you’re not rebuilding livelihoods, you’ve got to ask what you are doing. We’re very good at rebuilding things and rebuilding objects, but if we’re not creating livelihoods and education through doing that, then I think we have to ask what we are doing in any of these zones of fragility. We had the highest employability of any degree in the school because we accepted non-design cognate. So people came in from business, as long as they had an undergraduate degree or the, whatever was the equivalent in terms of practice.

0:42:09.1 Esther Charlesworth: Generally people who come in, they would need career. There are similar degrees. Carmen Mendoza, a friend of mine runs one at UIC in Barcelona, an emergency architecture degree, but they’re generally just graduates. My advice to anyone who wants to get in this sector, you really need to have 15 or 20 years of work. You need to know yourself, you need to have some technical skills. Getting into the international development work is as tough as getting into Shigeru Ban’s office. So this isn’t, and you get, will get paid less if you work in the not-for-profit sector. I’m open to, not open to office, but I live a long way away, but it’s a very ideological thing because the model of my school now is based on STAR Architecture, is based on award-winning buildings.

0:42:58.7 Esther Charlesworth: If I get told one more time, “Esther, you’re in such a niche or bespoke area,” I think I will scream. We are reading the news, I’m reading the New York Times last night about a cyclone and earthquake somewhere else. I was just somewhere else that had about three days ago, somewhere in a seismic zone. I felt the earthquake tremors. I mean, are you joking? Is this niche? Is this bespoke? One of my students who ran a very successful architecture firm who graduated in first class and he said, “Esther, I would’ve been a much better architect if I’d done these subjects in my undergraduate degree. Almost now, it’s too late.” There is time, but again, it’s the disciplinary chauvinism of the professions…

0:43:45.4 Julian Agyeman: The second online question, do you collaborate with any academics and architects worldwide?

0:43:51.4 Esther Charlesworth: First of all, Architects Without Frontiers only go where we are invited. So all the time people will say to me, oh, we’ve had a lot of floods in Australia and obviously bush fires. And people say, “Will you go up to the Northern rivers, Esther?” No, we had no remit to work there. Australia, we do have a big government. We do have people who will step in disasters, local versions of FEMA. We have to ask someone to come in. We are not flying people who are gonna solve a problem. We have a European group of like-minded schools from Belleville in Paris to Venice to Darmstadt to UIC Barcelona that we have brought… RMIT have a campus in Barcelona, that we are brought together. We were gonna put together, we did a big European grant. So I do work with consortias of other universities, mostly in Europe because the headquarters is in Geneva for a lot of these organizations.

0:44:50.1 Esther Charlesworth: And I think the UK is ahead of the curve in terms of some of this work. There’s Architects Without Frontiers UK who are really big. So this sort of work is far less foreign in that world. As I go back to it, we do not have the remit to work with refugees. My friend, Brett Moore, who was a Loeb fellow, until recently he was the head of Shelter and Settlement for UNHCR, we have to be very careful that we don’t go in… There’s a very well known architect who set up Architecture for Humanity and I saw him yesterday on social media, guess where he is? Gaza. Of course he’s there ’cause he was in Ukraine last week. And I think it’s pretty dicey because you do become this sort of ambulance chaser, dare I say. We are not invited to do those projects and nor would we because we don’t have the remit to work within them. In terms of political ethics, I think the project I showed in Dar es Salaam, architects want to win awards. They don’t want to listen quite often.

0:46:00.7 Esther Charlesworth: They want their projects built overnight and they’re not willing to compromise. We’ve got a 2030 strategy at the moment where we’re turning that around because we’ve got two staff, we actually need eight, and we need a full-time CEO. So, I think all the time they’re in ethical conundrums and one of the projects we’ve got two architects, indigenous housing is the theme du jour, saying, I can do this better than you ’cause we’ve got an indigenous architect on staff and it’s already getting messy before the project began. So, it’s a great question. The issues of refugees is an intractable one, having lived in Beirut and volunteered at the Palestinian camps most weekends, I can attest to that. I’ve been to al Za’atari in Jordan to understand how that project is working and a number of other camps. But it’s because of the land tenure and the lack of legal status, it’s a much bigger issue beyond my remit. But great question.

0:47:00.4 Jim: My quick question is the cultural and vernacular expertise needed to fly into these countries, you’re not flying in like Sir Norman on your private jet, but you are flying into a country where you may not be prepared to know the local building techniques, the culture. How do you bridge that and make things culturally and locally, you get it.

0:47:18.7 Esther Charlesworth: Great question, Jim. I wish I had a private jet, I wish. First of all, we always have a local project architect. We try to avoid liability by not building, but where we have in Vietnam and Fiji, all of the procurement of the materials is all done by local project management firms. So we might go over to scope the project initially. If it’s not built by locals and involves architects, some countries don’t have architects where we work, then we wouldn’t touch it with a barge pole. So every project is completely different. We’ve done sort of another 20 projects I didn’t show here, one in Chiang Mai for the Asian Indigenous Peoples Pact Coalition. They had a Thai architect, but he had no experience in sustainable construction or rammed earth that was being used. And we had a lot of expertise in that in a way, because if you just start exporting what I think is a good prefab technique in Australia, it might be totally the wrong solution on your island. But great question, Jim.

0:48:25.4 Loretta: I did some work recently on community architects in London, and obviously, they’re also architects who deal with kind of social engagement, bottom up grassroots architecture. I was interested in how both your research and your master’s module utilizes concepts from other architectural movements that are socially and community engaged and what they are.

0:48:45.8 Esther Charlesworth: Look, we are drawing on the giants of people like Jeremy Till and his book on spatial agency. And I know Jeremy well. Obviously, people like Cynthia Smith, who designed for the other 95%, this isn’t new stuff. There’s another book done by Maria Colino, who teaches in Paris on shelter and settlements. So I think the community architecture movement is an interesting one. I don’t know if you know Yasmeen Lari’s work? She’s in the book. So Yasmeen is the first female architect in Pakistan, who ran a corporate practice until the late ’70s, until the earthquakes in the late 1990s. She just said, “Then what am I doing? I’ve got to sort of give back.” So, Yasmeen has started off a movement called the Barefoot Social Architecture Movement. She’s got people building large bamboo structures and building their own houses. She’s very anti-foreign aid, that the locals should be doing it themselves.

0:49:48.9 Esther Charlesworth: So I think, it’s hard to say community architecture per se, ’cause I think we have to look at the countries in which they’re being built. But Yasmeen is a great case study in this. Yasmeen got the Royal Institute of British Architects gold medal two years ago. She’s a complete legend and I’m interviewing her for the Australian Institute’s conference next week. And she came as a visitor to the MAUD degree and had all of our students building bamboo structures all day. I think the grassroots community architecture is incredibly important, but I wouldn’t put a box around it. Because once you start to put a box around what is social architecture and what is community architecture, we might run into a few problems ’cause some people would say, that’s exactly what we’re doing. Norman Foster might say that’s what he’s doing. I don’t think he is, but great question, Loretta, and I’d love to read your book.

0:50:47.4 Speaker 11: I found that point that you made about hard design and soft design, physical design and people’s needs design, really thought provoking. And so that made me think of, is there work that Architects Without Frontiers is doing related to the ownership of the structures? And I can imagine that can be very ambitious and difficult thinking of who has the ownership of these buildings. But I’m wondering if that’s anything that y’all consider in the design.

0:51:13.4 Esther Charlesworth: Yeah. Great question. The issue of tenure is a really thorny one. Now, I should just say on our website, people fill in a project request form. Do you have funding? Do you have land tenure? So we do not resolve funding. If people don’t have legit tenure over their land, we would not take on board the project. We have to be very careful what is the remit of our organization, what do we do and what we don’t do. And by a former Foreign Minister of Australia, Gareth Evans, an incredible figure who also ran the International Crisis Group for 20 years in Brussels when, he’s one of the ambassadors for Architects Without Frontiers and he said, is to be very careful to be very limited in what is the remit of your organization. So no, we’re not dealing issues with land tenure. We then do a whole lot of our workers in the return or the reverse brief. Is this project needed? Are we dealing with a right wing Christian organization?

0:52:15.2 Esther Charlesworth: No, we don’t wanna do the project. Are we dealing with nuclear arms? Are we dealing with some sort of psycho whatever? I don’t know how you’re all gonna work out that one. But we do, a lot of our work goes into the due diligence because otherwise, it’s a waste of that person’s time. We wanna build these projects. These aren’t just sketches. And that’s why on the smell of an oily rag, until two years ago, we had one paid staff. Now we’ve got 2.5, hopefully with philanthropic funding, which is a completely different structure in Australia, we don’t have tax breaks. It’s very hard to get funding because it’s assumed the government will give you funding. So we don’t deal with tenure because it has to be sorted out before we take on board a project.

0:53:08.4 Speaker 12: Esther, this was an amazing presentation and I so much value the organization, your answer to some of these questions about the due diligence as an organization. So I wanna ask a slightly different question. It’s not a critique at all of the organization, but what I’m… I wanna speculate a little bit more about where this kind of work could be taken and redeveloped in urban studies more generally. And before I ask the question, let me just say that I used to run a track at the GSD called Risk and Resilience, which our dean got rid of too, which was looking at the same thing. So we’ll have to have an offline conversation about the ways in which the discipline of architecture is not willing to enter into the social urbanism space. So I think that’s a part of the issue that you’re probably dealing with, but that’s exactly what I wanted to ask you about though. Are there lessons to be learned from the work that you’ve done that move us into the social urbanism space? So one of the limitations of architecture historically, and I would say in, especially in the global South and a lot of these places, looking at it on the US, is the kind of obsession with the house, the building itself and not the neighborhood.

0:54:30.4 Speaker 12: Maybe picking up on what Loretta was talking about, community design. And I guess my question is what can we learn? How can you share the knowledge you have of these spaces to take the field work and the knowing how to work with communities and turn the product into something larger and bigger with more impact, maybe sustainable impact than the house itself. So pulling you into, back into the urban design realm in architecture, going beyond just the building to urban design. And the second question builds, again, that I thought of Loretta’s question about community, I was thinking about, or was conversation about ethics. I’m wondering whether we should be following these models in American cities, and what do I mean by that? Part of the problem of disaster inequality, kind of inability for families to be resilient has to do with the way property markets work and architecture builds those markets, right?

0:55:35.6 Speaker 12: And what is striking about your work and with Architects Without Frontiers is the small scale. So I’m maybe sound like I’m contradicting myself, the focus on the house, but the idea that you can innovate in a relationship with a consumer of that piece of architecture based on what they need, having aesthetics and local vernacular things, but not falling into the trap of mass produced big housing, which just reinforces, you know, pushes people out and inequality, et cetera. So I guess, do you have some thoughts about how this work that could be easily, I don’t wanna say easily ghettoized as like othered, as in big disasters and in the developing world we could learn about that and bring that back to cities like Boston or New York or London or the global North, so to speak. And could the staff that you work with, could you share knowledge that we could use in kind of the everyday crisis of urbanism and not just a disaster?

0:56:52.6 Esther Charlesworth: I’d like to hear a lecture on this, what a question. I’d like to say that we’re designing a system, not always a project. Architects are de facto psychiatrists. People quite often don’t know what they want. Now, I don’t know how people come to us. It must be an algorithm. Architects without money because why are people coming in from East Africa or wherever, quite often groups from America and asking us to do projects. So the second point is we don’t do residential because we simply haven’t been asked. And so that’s why we largely avoid this sort of tenure system. In terms of the social urbanism, the landscape, the small scale, I’ll get onto that. So the project I spoke about, the new indigenous housing project up in Ramingining, the first thing I did was bring on board a landscape architect with a great knowledge of the ecology of that coastal soil because one of the big problems is, is houses, is they’re plunked on the ground with no understanding of the coastal environment and the erosion.

0:58:03.2 Esther Charlesworth: So our offices actually in Melbourne which is the largest landscape architect in Australasia, I wish I’d done MLAUD maybe rather than MAUD. In urban design, the best urban designers I met are the landscape architects. I’m not saying that there aren’t egos in that profession, but that they’re a lot less. So that is one thing, designing a system. We are not generally doing houses, but involving landscape architects from the outset. In terms of how we take this and sharing knowledge, maybe that’s the next part of the journey. For us, the critical thing is now looking at the impacts for the projects. How do we quantify the impacts? We know if you work in health, that your metric is infant mortality or maternal mortality. If you’re in education, it might be truancy. In design, on an existential level, how do we know what we know and according to whom? And while there are, particularly in the UK, Loretta, there’s some interesting stuff coming up about design impact. The funding thing completely changes.

0:59:11.6 Esther Charlesworth: And this is what Brett Moore was dealing with UNHCR with the Better Shelter Project, which is the largest mass shelter project in the world funded by the IKEA Foundation because they’re on version 12 of it now. So I think it’s a sort of an iterative thing. And I, as Julian pointed out, I’m on the board and one of the founding groups of Architecture Sans Frontières International, which is an umbrella group of 43 organizations. There is no American group, there’s ASF Quebec. And I guess because Architecture for Humanity took up all that airspace and then went down in flames and they were membership-based organizations. So in a way, organizations like that, Engineers Without Borders have been great because they’re membership-based organizations, they’re in the universities. I think once, for me that the next stage, perhaps academically but also project wise is to be able to say of our 62 projects, these have been the quantifiable impacts because then you are speaking a different language to the funding agency.

1:00:20.4 Esther Charlesworth: If you can say that this kind of housing design will reduce the incidents of, we can’t say school leaving but of disease as we know through the MASS Design’s Group work in East Africa, then you attract a different kind of audience. So I think that is my big challenge. And I think it’s just small by small. We don’t aim to get really big and it’s an ethical decision as I said, do we just talk about things, so blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, or do we do things? And in the last, not some, in the last stages of my career, but at this point of your career, there is a sort of a reckoning. You can’t do everything and where are you gonna be most effective? And I think we all feel the pressure of that in academe. It’s a great question.

1:01:08.8 Julian Agyeman: And this was our first Cities@Tufts Boston Urban Salon event. I’m hoping we’re gonna have more. And again, Esther, this has been wonderful. We haven’t had an architect actually talking in the Cities@Tufts program, so you brought a whole new set of perspectives. And again, thanks very much.

1:01:27.4 Tom Llewellyn: We hope you enjoyed this week’s presentation. Click the link in the show notes to access the video, transcript, and graphic recording, or to register for an upcoming lecture. Cities@Tufts is produced by the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University and Shareable, with support from the Barr Foundation, Shareable donors and listeners like you. Lectures are moderated by Professor Julian Agyeman and organized in partnership with research assistants, Deandra Boyle and Grant Perry. Light Without Dark by Cultivate Beats is our theme song and the graph recording was created by Anke Dregnat.

1:02:00.9 Tom Llewellyn: Paige Kelly is our co-producer, audio editor, and communications manager. Additional operations, funding, marketing, and outreach support are provided by Allison Hoff, Bobby Jones, and Candice Spivey. And the series is co-produced and presented by me, Tom Llewellyn. Please hit subscribe, leave a rating or review wherever you get your podcasts and share it with others so this knowledge will reach people outside of our collective bubbles. That’s it for this week’s show. Here’s a final thought.

1:02:28.4 Esther Charlesworth: Poverty does not exclude aesthetics. Most of these projects won design awards. This is not a game of aesthetics, you can be doing both.

[music]