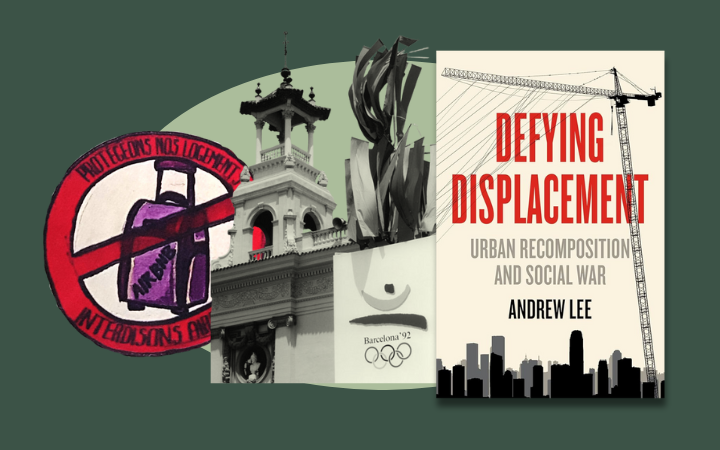

The following is an excerpt adapted from Defying Displacement: Urban Recomposition and Social War (IAS/AK Press, 2024).

Holiday in the sun

The politics of place and displacement follow gentrifiers on holiday. Depending on the balance of class interests and power, the unique character of a place can attract gentrification as much as it can be wielded as a weapon against it. Charming Barcelona’s tourist-centered redevelopment started in earnest during preparation for the 1992 Olympics and intensified when the Convergència I Unió party rezoned swathes of the city to attract international capital in the depths of the Great Recession. Today, Barcelona has reached an “acute” state of gentrification thanks to the appeal of its “historical heritage, cultural dynamism, business economy,” and beaches. “The neighbors are disappearing,” reported one resident, saying rents had increased 200 Euros in recent years. “They are leaving.” But tourism is now a “fundamental industry,” per the managing partner of a hospitality consulting firm. “Many directly or indirectly connected industries would suffer greatly without it.”

With Airbnb, landlords around the world can easily replace tenants with tourists, multiplying the amount of money they receive each month. A San Francisco landlord evicted a tenant paying $1,840 a month to charge tourists twice as much. Airbnb rentals are estimated to have raised average rents in New York City by $400 a year. The platform has faced pushback in cities from Amsterdam to Venice as housing units are reserved for globe-trotting tourists.

The international vacation destination ought to be foreign and exceptional — nothing less justifies the airfare. But it must also make sense to the vacationer. There must be appealing hotels easily booked, attractions advertised in an understandable way, staff who speak their language, restaurants with menus that fit their tastes. As Guy Debord pointed out, tourism is “the opportunity to go and see what has been banalized,” commodified, made legible and essentially equivalent to any other vacation destination one might choose.

This tourism gentrification, which carves up working-class neighborhoods to attract vacationers’ dollars with hotels, resorts, restaurants, and shopping districts, is less frequently discussed in the United States, perhaps because the nation’s intellectuals and academics find themselves partaking in the practice on holiday. This is unfortunate, since tourism gentrification has come home to roost in devastating ways. The 1996 Olympics provided Atlanta elites with the opportunity to clear poor people from central areas, decimate public housing, and brand the city for global consumption, paving the way for today’s rampant gentrification. The 2028 Games in Los Angeles are already creating a “housing disaster” years in advance. The Philadelphia city council voted 12-5 to approve a downtown basketball arena threatening to destroy the local Chinatown, against the wishes of 69% of residents and after arresting dozens.

Homeland or death

The fully engineered tourist district attracts huge amounts of foreign capital that can anchor the economy of an entire region or nation. Land was legally bought and sold in post-revolutionary Cuba for the first time in 2011. Though non-Cubans are formally excluded from the market, it is reported that many property sales are funded with remittances from Cuban American relatives or conducted by Cuban citizens operating at the behest of foreign buyers.

Almost two decades before the establishment of a real estate market, the Cuban state began emphasizing tourism as a way to attract foreign capital. In the early 1980s, several buildings in Old Havana were recognized as UNESCO World Cultural Heritage sites—a designation supposed to recognize the objective importance and international legibility of a place while facilitating economic and technical assistance for historic restoration. During the economic devastation of the post-Soviet “Special Period,” when petroleum imports to the island virtually ceased, the state developed public institutions to promote tourism while dilapidated colonial buildings were transformed from residential units into restaurants and luxury hotels. Former residents were directly displaced to the city’s outskirts. Even while the ban on real estate speculation remained, the increased valuation of Old Havana real estate was expressed in the informal market. Remaining tenants began renting out rooms or running small businesses that benefited from easy access to the tourist market. (Access to foreign currency is so significant that Cuban taxi drivers can make more than surgeons.) In 2001, 40% of residences were free tenements; by 2019, it was only 12%, with 75% of residences in touristified Old Havana now private property. If privatization and tourism-oriented redevelopment is the priority of a state whose foundational narrative is the revolutionary expropriation of private property, it should be no surprise when US state elites find economic incentives more convincing than purported liberal commitments to “inclusion,” “diversity,” or “the community.”

Andrew Lee is the author of Defying Displacement: Urban Recomposition and Social War. Lee has supported grassroots social movements for more than 15 years and his work has been published in outlets including Teen Vogue, Yes! Magazine, and The New Inquiry. He writes at In Struggle and is a board member of the Institute for Anarchist Studies.